I see it all the time. A speaker presents a word-dense slide deck. As an audience member, I try to read the words and listen to the presenter at the same time. Occasionally I can manage that, but usually it’s one or the other, and I end up reading the slide and ignoring the speaker. Before I can finish reading the next slide is up. I’m frustrated and the speaker doesn’t even know that I’m reading and not listening, and it’s quite possible they’ve lost the entire audience’s attention.

The human brain does a poor job taking in dense visual and oral information at the same time. A deck that is presented live should support the speaker, augment what is being said, and maybe leave a visual impression that sticks (it’s been shown that most humans remember visuals better than hearing or reading words). It doesn’t need to be a self-sufficient, complete work.

So instead of being word dense, the deck should be like a highlighter – showing only key points or images that reinforce or make memorable what the speaker is saying.

However, often a deck has to be shared with or sent to someone without a presenter. In this case, it’s essential that the deck is able to stand by itself in telling the complete story – since no one will be there to explain it orally.

So a really smart approach to preparing important decks is to make two decks – a word-light version that accompanies a speaker, and a content-dense stand-alone version for distributing on its own.

Here’s another reason for two decks. When you present a deck, you control the order that the story gets told. So when you present the solution, you know the audience has just heard you describe the problem.

However, when you send a deck out on its own, you can’t control what the reader reads or in what order. He or she may look at your title slide and believe they know what problem you must be solving, so they may skip right to your solution slides. This means that each slide must be able to stand on its own, and perhaps certain key information should appear on different slides, even though that information was already presented.

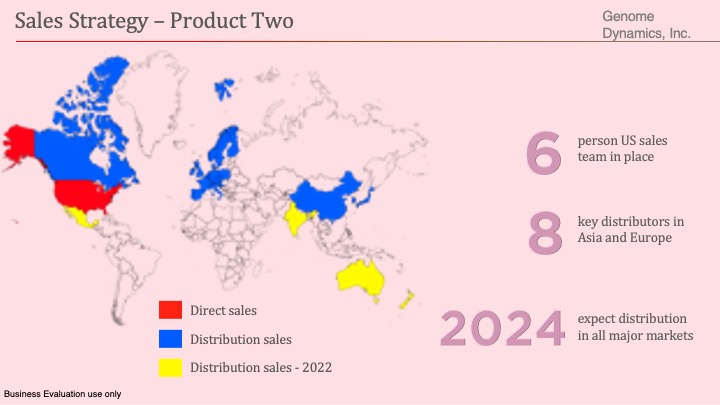

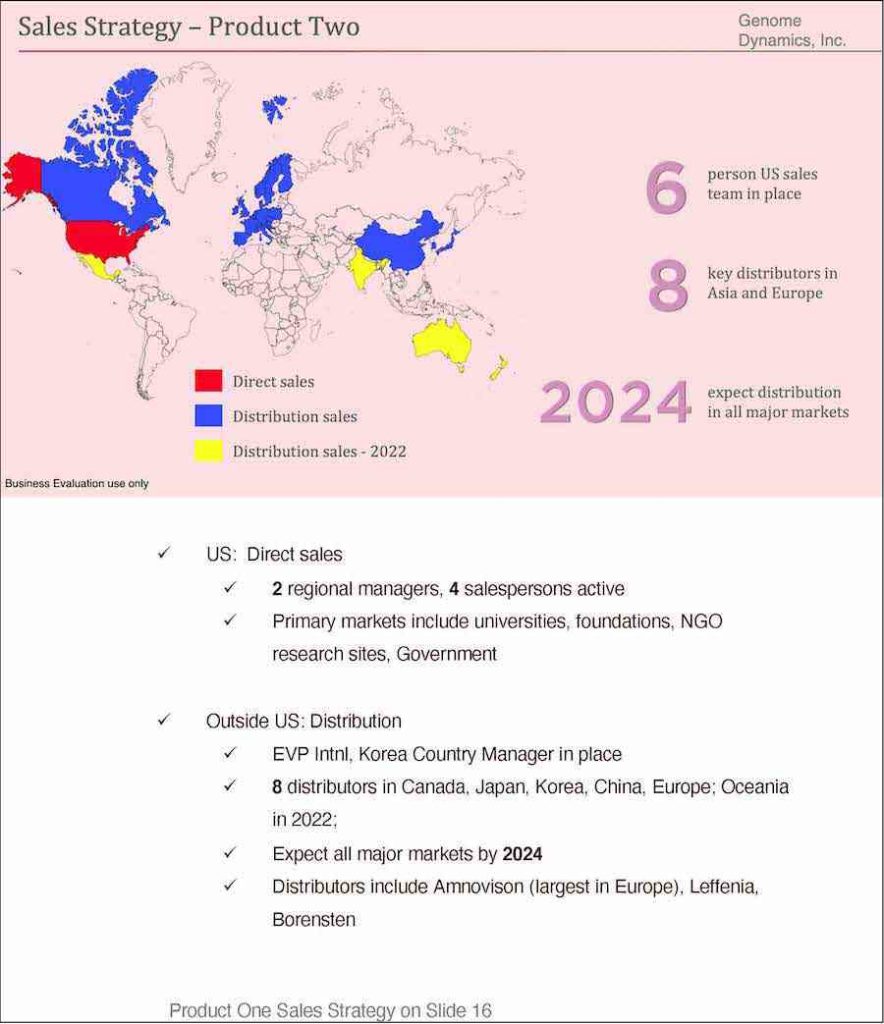

The following two slides are two different approaches to the same go-to-market information. We’ll call the first slide the “Leave-behind” slide, and the second the “Presentation” slide.

Both slides convey the same key points: the company has clear plans for distribution of Product Two throughout the world, selling directly in the US and via distributors elsewhere, and that the firm has clear traction, having built a US sales team and signed distribution agreements with major distributors elsewhere.

Notice that the Leave-behind slide says all the above, and is therefore pretty content-dense. Also note that it mentions that this plan is for Product Two, and that Product One’s plan is shown on slide 16. This is stated explicitly because the author has no way of knowing if the reader is viewing the slides in order, or just skipping to this slide, or may have received only this single slide from a colleague.

The Presentation slide has far fewer words and focuses more on the visual map, which conveys that the company “covers the world.” Also, notice that whole sections in the Leave-behind slide are replaced with a single memorable image or phrase. So instead of naming the distributors that are engaged, the phrase “8 key distributors” is shown, with an oversized and 3-D “8.” The speaker will mention the names of several of the distributors and the audience will hear this and not be distracted by a lot of text. But hopefully the audience will remember that 8 distributors are on board.

To save time and be almost as effective, you could create just the Presentation deck. But you use the notes section to add the information to make the slide independent and complete. Then, you include the notes when you send it as a Leave-behind deck. The upside is that this is easier to do than to maintain two versions of your deck. The downside is that some people will only look at the slide and not the notes. Generally I think this hybrid model is a good balance of effort vs. effectiveness.

Some people try to “split the baby” and intentionally create one deck, with more detail than ideal for a Presentation deck, but less detail than ideal for a Leave-behind deck. Sometimes this can work, but it kind of reminds me of those packages of instant coffee mixed with fresh ground coffee. Instead of the convenience of instant and the taste of fresh ground, it usually ends up being the price of Starbucks with the taste of instant!

It’s a lot of extra work to create and update two versions of a deck. But if the need to persuade your audience is extremely important, and you’re fortunate enough to be able to present your deck and have someone read your deck when you’re not present, it’s usually the best way to succeed.

0 Comments